The face of equality takes many forms... political equality, equality of opportunity, treatment, membership and perhaps more controversially equality of outcome. If this state of being equal is a core value in the democratic tradition, does it follow that the responsibility to achieve it lies in a collective determination?

How then can the architectural process contribute, indeed should it seek to?

Once hailed as a master craftsman, an age of humility is dawning. The role of the architect continues to evolve and a growing underbelly is challenging all we hold to be true. Has the profession focused on providing design services for the top percentile for too long? Can the sector reclaim a sense of social responsibility and if so what methodologies should be celebrated?

Architecture, good architecture, is not about the end product. It is not about a series of components eloquently assembled. It is the life that pervades around it and the sense of community created in and through the design thinking, which brings the object to life.

A shift in process is required. The power of architecture can be realised if citizens take ownership – the architect as the facilitator; the client as the agent of change.

The architectural process begins well before pencil meets paper. Engagement with the end user is essential to understanding real needs. In Mumbai for example, non-governmental organisation SPARC seeks to mobilise pavement and slum dwellers, equipping groups with the tools they need to articulate their concerns and create collective solutions. The once invisible urban poor are supported in direct negotiations with the government, cementing their right to the city.

Early design development is all too often resigned to brief discussions and back of house iterations. A human-centred design approach incorporates a myriad of tools, which bring architecture back to the public domain and in doing so support capacity building. For example, community workshops running in parallel to the design journey are a key aspect of SAFE’s work. This small Bangladeshi organisation strives for replication of improved construction techniques in an area on the frontline of climate change. With limited funding, their projects will only be successful if information is disseminated widely, if ideas are presented in a culturally sensitive manner and if the local population chooses to engage. It is not enough to provide a handful of families’ access to adequate shelter. The vision must empower the wider community.

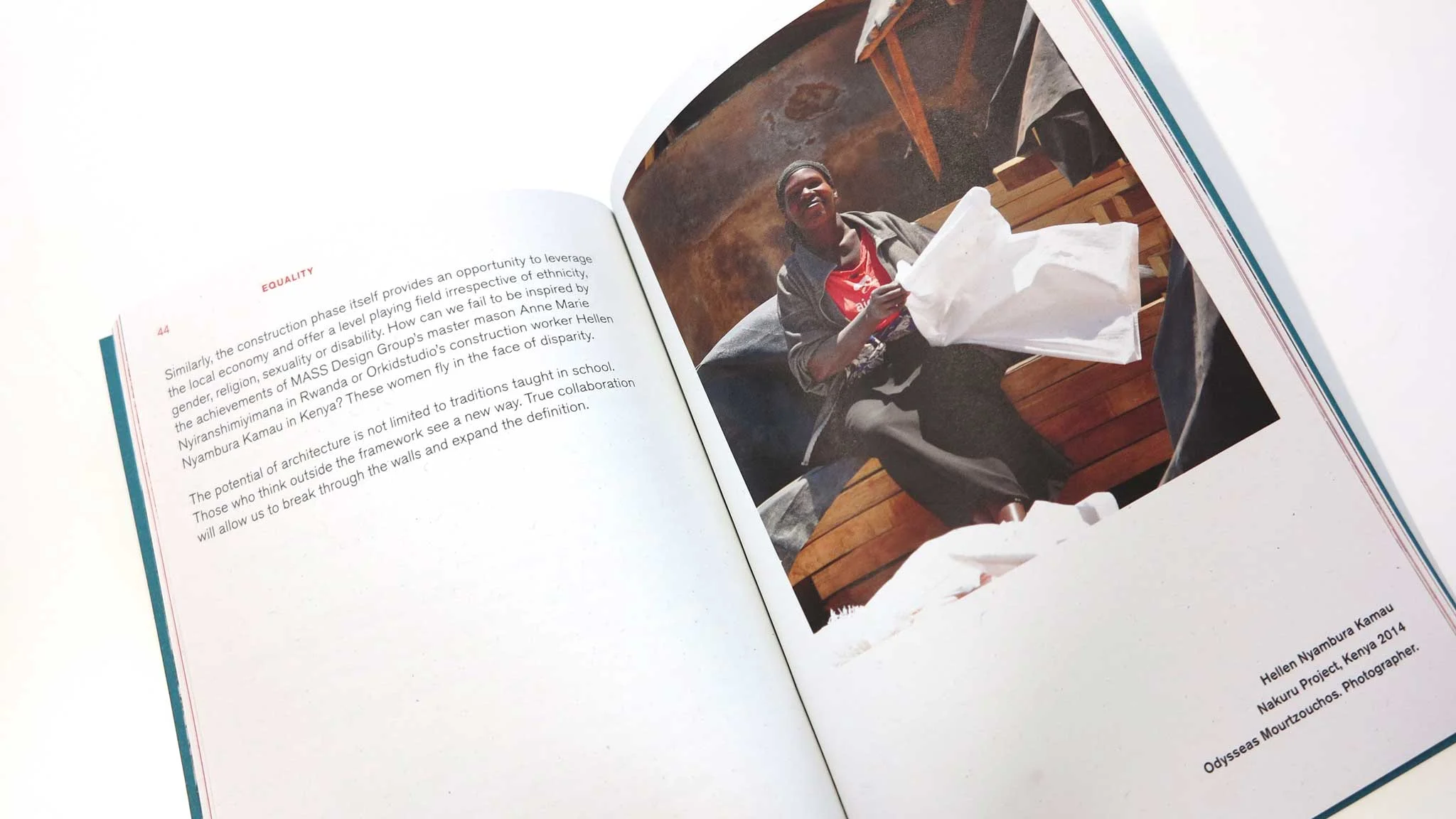

Similarly, the construction phase itself provides an opportunity to leverage the local economy and offer a level playing field irrespective of ethnicity, gender, religion, sexuality or disability. How can we fail to be inspired by the achievements of MASS Design Group’s master mason Anne Marie Nyiranshimiyimana in Rwanda or Orkidstudio’s construction worker Hellen Nyambura Kamau in Kenya? These women fly in the face of disparity.

The potential of architecture is not limited to traditions taught in school. Those who think outside the framework see a new way. True collaboration will allow us to break through the walls and expand the definition.

Think beyond the building. Think equality.

Author: J. Ashbridge