In 1921, the former Mayor of Poplar (now Tower Hamlets), spent six weeks in prison for directly defying the London County Council. His offence: defending the equal taxation rights of his constituents in East London - at the time (and still today), the most deprived and unjustly taxed in the city. His name was George Lansbury.

Lansbury's name lives on through his granddaughter Angela and through the neighbourhood that bears it.

“Could you imagine a politician today going to jail for something they believe in?”

We're part of an ongoing conversation with those who live in and around Poplar for our A sense of place project.

Chrisp Street Market (the symbolic centre) stands at the precipice of regeneration, and at the forefront of what Lansbury fought so dearly to counter - a lack of concern for the most vulnerable. It's an apt forum for the London Festival of Architecture's 2017 theme, 'memory'.

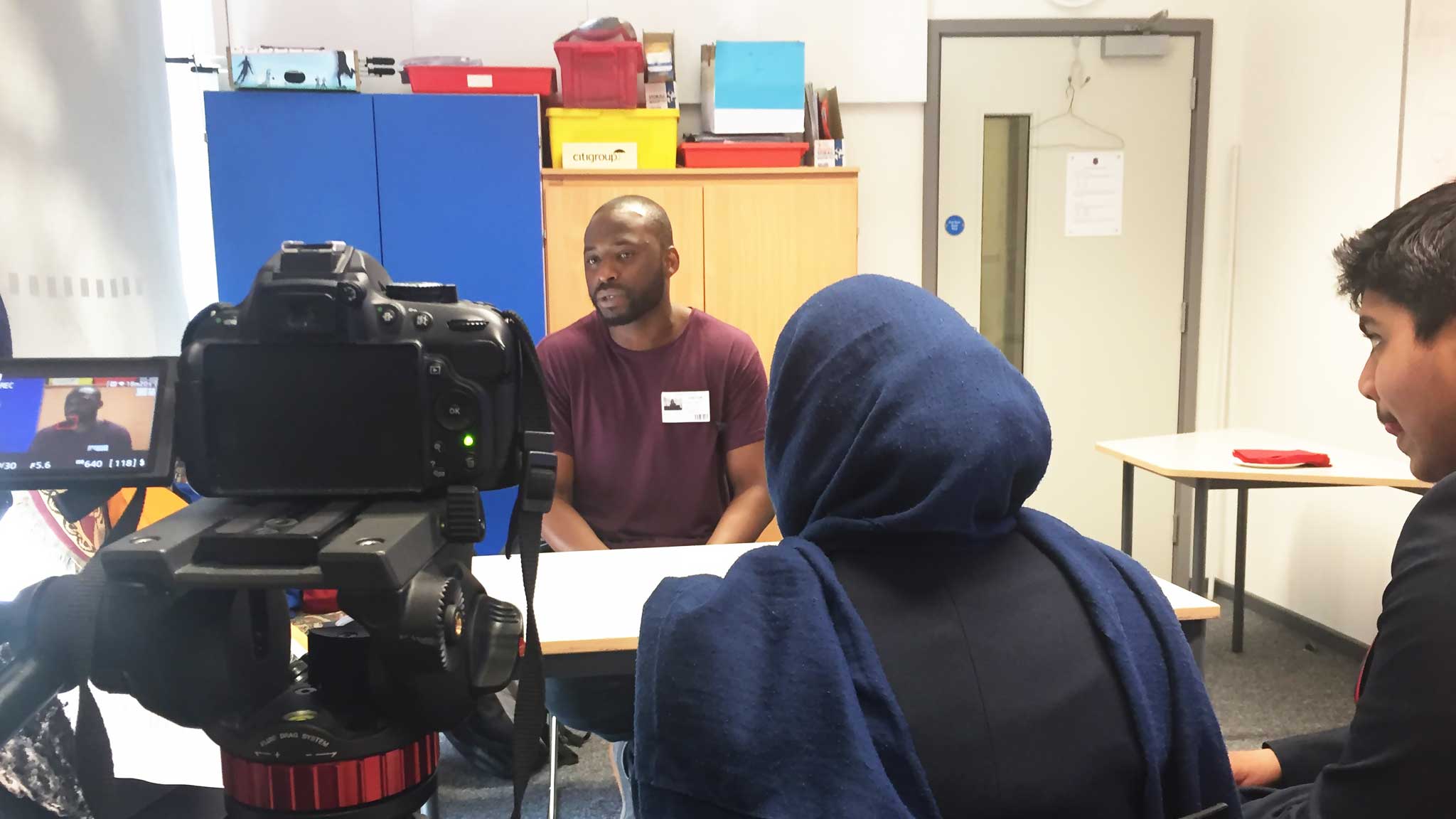

As part of the festival, we hosted a range of individuals from researchers and architects to local residents and volunteer groups at Kafe 1788. Together we explored how to reduce the rate of eviction among residents of social housing, and how to build resiliency. The outputs from these co-design workshops were then added to an exhibition of our work in the Poplar Pavilion, designed and built by Wellcome Trust Engagement Fellow, Alex Julyan.

(Elicea Andrews Photography - additional event photos)

Responding to stories of those we've spoken with - their hopes and fears - we used activities driven by empathy to lead discussions about belonging and community. What does placemaking look like when everyone is included?

Groups addressed three questions:

How might we support residents to better understand their tenancy rights?

How might we more clearly communicate the pressing concerns and challenges of residents to social landlords?

How might we include the most vulnerable in placemaking activities?

In brainstorming answers to these questions, it soon became evident that building trust and respect between tenants and landlords is paramount, whether through 'gastrodiplomacy', 'local champions', 'persistent contact', 'face-to-face', 'personal advisors' or even a 'listening service'.

The groups also placed importance on existing skills, strengths and capacity of residents, where such assets can be shared and how to support residents create their own trusted networks.

'Space' and 'place' were embedded in every conversation.

At AzuKo, we believe that the process of coming together to express and share ideas is a worthwhile experience for all those involved. Feedback from our event showed just that.

Participants told us:

Empathy is a necessary starting point for design

Insights driven by residents create meaningful solutions

There is value in learning from others' experience

Role play is a great tool to see the world from another's viewpoint

Participation, collaboration and diversity are key

LFA 2017 was a small sample of what happens when,

“you see the likeness of people in other places to yourself in your place. It lights invariably the need for care toward other people, other creatures, in other places as you would ask them for care toward your place and you.”

It was another small step towards the ends that George Lansbury fought for nearly a century ago - dignity in design.

Find out more about our project, A sense of place.

Author: N. Ardaiz

A very warm thank you to everyone who made our LFA 2017 event a success, including Alex Julyan (Wellcome Trust), Ao Leal video production, Elicea Andrews Photography, Justin Brown (native north architects), Kafe 1788, Kineara, Ruth Baker and Francesca Tafi (Ryder).